Updates

After I (GCP) wrote this, I went to the Maryland Hall of Records in Annapolis to get better-quality copies of some of the sources. (I had used transcriptions found here and there online, but I wanted to see the originals and transcribe them myself.) I didn’t have time for new research, but while photographing documents I found something surprising.

In my original investigation two different approaches, a surname analysis and a broad search for documents mentioning George Ramsden and John Parkin(s), the merchants “of the Kingdom of England” who were involved with Richard’s transportation, both had led to the same conclusion: they must have lived in Yorkshire. The Maryland court had only said they were in the “Kingdom of England” but not where in England. Other clues had been needed to narrow it down to Yorkshire specifically, and they had made it possible to find our family in Halifax.

But in Annapolis, to my surprise, I found a second lawsuit that mentioned these same English merchants. When I originally wrote the previous pages, I had only found the first.

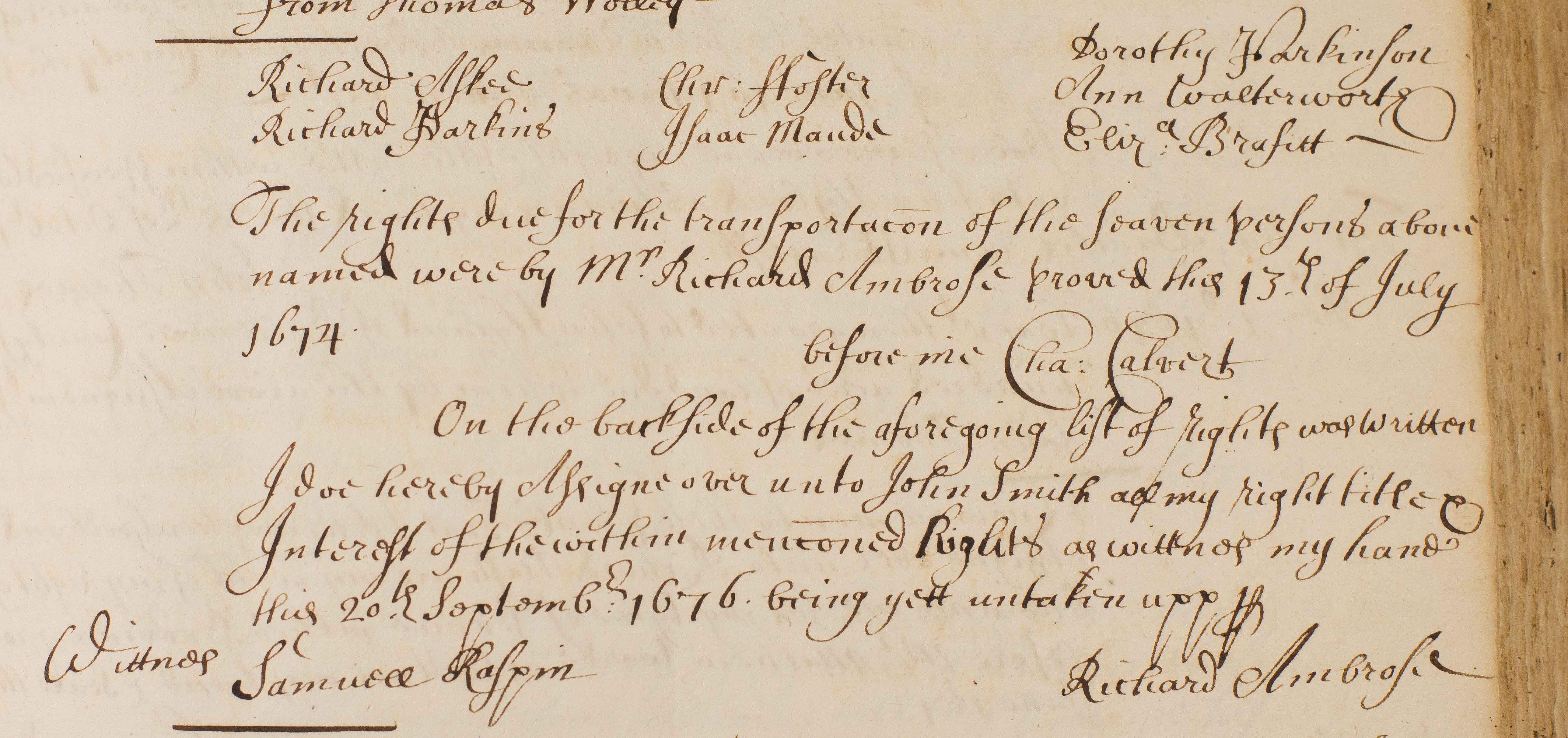

Here again is the record showing the transportation of Richard Parkins and his fellow passengers, which had taken place in 1674. The Maryland merchant, Richard Ambrose of Charles County, had been awarded the headrights for the transportation, and his transfer of these headrights in 1676 was witnessed by another merchant from Charles County, Samuel Raspin.

Maryland Hall of Records, Annapolis, MD: Land Office Patents Liber LL (1673-79), p. 512.

(Photo by GCP)

An update on this document: Richard Parkin and his fellow passengers arrived in Maryland sometime in the first half of 1674. In July an administrative court was convened in St. Mary’s City at which Gov. Charles Calvert (son of Lord Baltimore) presided in his additional role as secretary of the province. (You can see Charles Calvert’s name on the above transportation document. Charles County, where Richard “Parkins” would be living, was named for this Charles Calvert.) Calvert certified that Richard Ambrose, a merchant from Charles County, was legally entitled to the headrights for the transportation of Richard Parkins and six others and issued a warrant that was presumably worth 350 acres of land (seven people at fifty acres each.) In September 1676, Ambrose wrote on the back of the warrant that he was assigning these land rights to John Smith as one might endorse a check by signing it on the back. Since Parkins would end up making barrels in Charles County, this John Smith may have been the John Smith who was a carpenter in Charles County. This endorsement was witnessed by Samuel Raspin, another merchant from Charles County.

Between Richard’s arrival in 1674 and the transfer of headrights to John Smith in 1676, several things happened. Lord Baltimore (Cecil Calvert) died in England. He had never visited Maryland. His son Charles Calvert, who had signed the record of Richard’s arrival, became the new Lord Baltimore. In 1676, Bacon’s Rebellion broke out in the Chesapeake Colonies in which dissatisfied former servants burned Jamestown and threatened to topple (Lord) Baltimore’s government. The new Lord Baltimore, decided that something had to be done about the headrights system. Tobacco prices were collapsing, and a black market in headrights warrants that avoided taxes and fees meant he wasn’t getting paid.

So in 1676 Baltimore (again, by 1676 the son Charles Calvert had become the new “Baltimore”) tried to clean up the mismanaged headrights system. In late 1676 (by their calendar, which ended in march, but early 1677 by our calendar), the court copied the text of this warrant (front and back) into an official register, presumably so that they could keep better track of who had been issued what land warrants. The photograph above is of that original court register, now called Liber (book) LL, Folio (page) 512. But around the time this was written, Baltimore announced that the use of headrights to bring in indentured servants would be discontinued by 1678. He was fed up and wanted no more rebellious servants who weren’t even profitable to him when they weren’t rebelling. He was fed up with corrupt Land Office officials, too. But despite Baltimore’s announcement, the corrupt officials who were profiting by issuing land warrants—it was like printing money—took until 1683 to completely shut down the headrights system.

Richard Parkin had made it just in time. Shortly after signing his headrights warrant, Charles Calvert shut down the headrights program that had brought him to America.

In 1726, fifty years after the register we now call Liber LL was created, it was getting old and needed to be preserved, so it was transcribed (copied by hand), becoming Patents Liber 15, Folio 378. Over the next century, that copy got old, too, and in 1836 the copy was copied, becoming Liber 15, Folio 519. But the above is the original 1676 register (later bound into Liber LL), written with quill pen and iron gall ink at the end of Bacon’s Rebellion while our first American ancestor Richard Parkin was still a 22-year-old indentured servant in the proprietary province of Charles Calvert, Lord Baltimore.

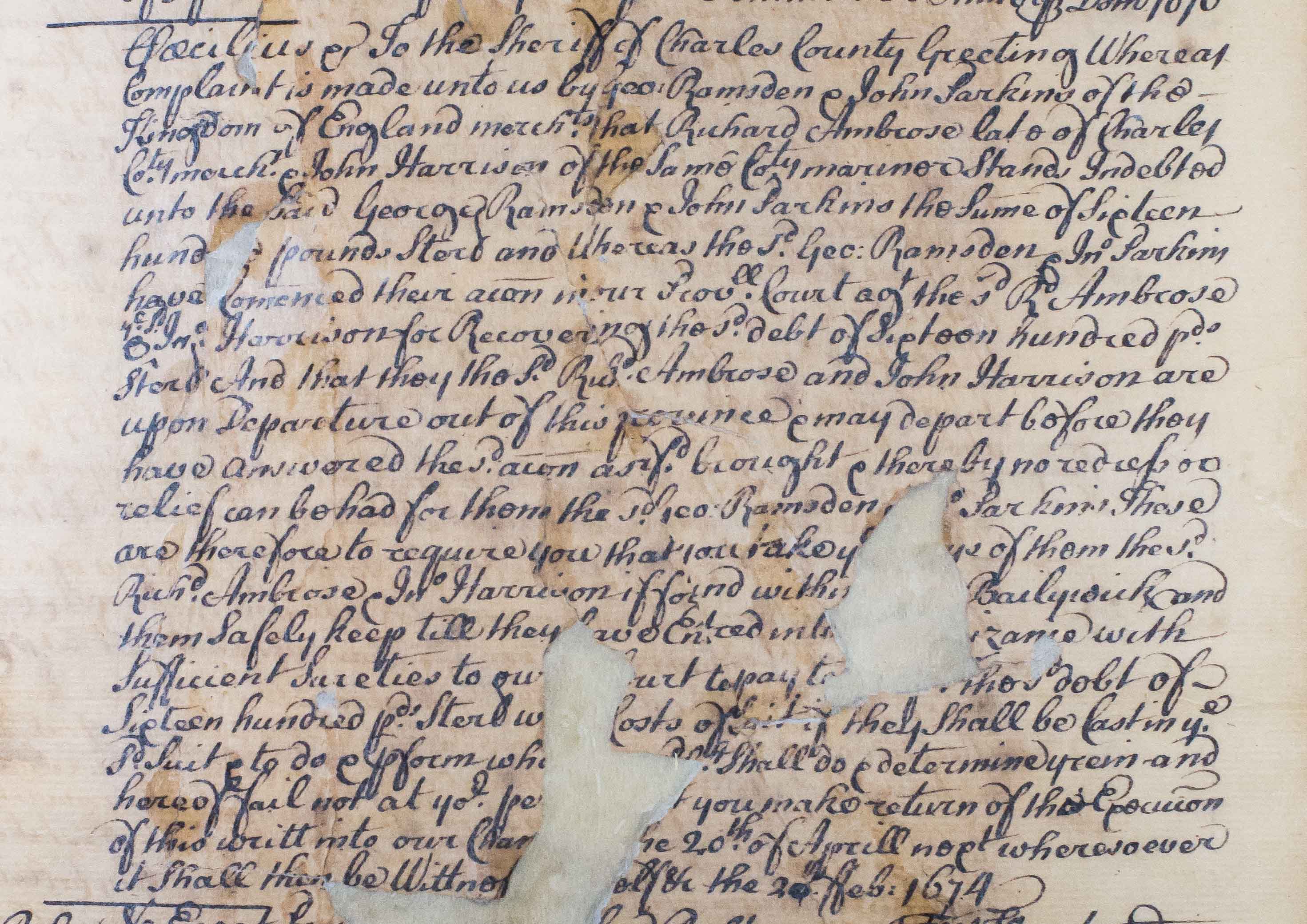

And here again is the first lawsuit, the one in which Richard Ambrose was sued in 1676 by “George Ramsden and John Parkins of the Kingdom of England[,] merchants” over a deal in 1674 that included merchants, mariners, brokers, servant laborers, transportation, and payments in both tobacco and cash. The English merchants were claiming that the Charles County, Maryland merchants owed them money. The details of this complex deal don’t matter at the moment. We’re interested in who the people were:

Maryland Chancery Court Proceedings 1676, Liber CD, Folio 181, a transcript of which is available from the Maryland State Archives.

(Photo by GCP)

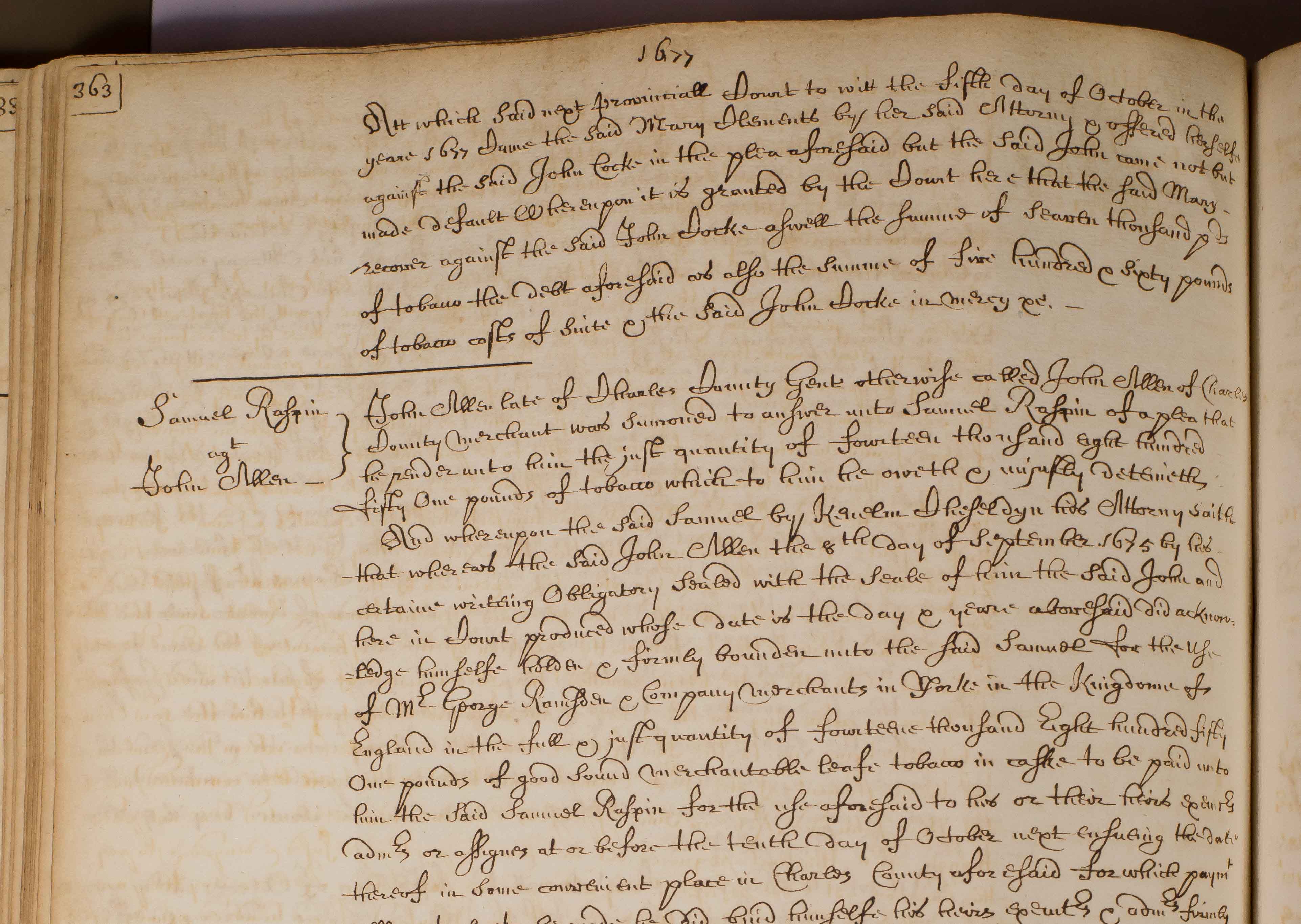

Ambrose probably didn’t pay. He apparently died later that year. But there was a second lawsuit the following year (in 1677) that mentioned these same English merchants and involved the same Samuel Raspin whose name was on Richard Parkins’s transport record. John Allen was the original owner of Allen’s Mill in Charles County, where Richard Perkins may have worked as a cooper. Allen was apparently having trouble paying his debts, so Samuel Raspin and others sued him. By 1680, Raspin was running Allen’s Mill and owing money to Richard Perkins (possibly back pay), but in this lawsuit in 1677, Raspin complains that he needs the money that Allen owes him to pay his own debts to some merchants in England. These are the same merchants who were suing Ambrose the previous year—merchants referred to in the previous lawsuit as, “George Ramsden and John Parkins of the Kingdom of England[,] merchants”. In this lawsuit, Samuel Raspin refers to them as, “Mr. George Ramsden & Company, merchants in Yorke[shire] in the Kingdome of England”.

Provincial Court Proceedings 1677, Liber NN, Folio 363, a transcript of which is available from the Maryland State Archives.

(Photo by GCP)

(Start at the bottom, go up the left edge of the text about six lines: “Mr. George Ramsden & Company merchants in Yorke[shire] in the Kingdom of England”.)

Samuel Raspin was claiming that back in 1675 Allen had agreed to pay him money that was owed to the English merchants. In other words, Raspin was saying that something had already happened by 1675, the year after Richard Parkins was transported, for which Raspin had to pay George Ramsden and John Parkins in Yorkshire.

With this new document, we have the following timeline. Remember that the reason for all the debt was that they had things of value (labor, food, housing, tools, transportation, land) but almost nothing that could be used as money for immediate payments. They had to keep track of debts until a “liquidity event” such as a tobacco harvest or a ship arrival allowed them to pay each other.

- 1674: Richard Parkins is transported to Maryland by Richard Ambrose, a Charles County merchant.

- 1675: Samuel Raspin, another Charles County merchant, owes money to George Ramsden and John Parkins back in Yorkshire, which he needs to collect from John Allen, owner of Allen’s Mill.

- 1676: Ramsden and Parkins sue Ambrose (from England) for non-payment, but Ambrose dies.

- 1677: Raspin claims he still owes money to Ramsden and Parkins back in Yorkshire, which he still needs to collect from John Allen.

- 1678: A “gentleman” named John Jones dies and lists debts to both Samuel Raspin and Benjamin Rozier (among others). The debt to Rozier is said to be money originally owed to Richard Ambrose, but Ambrose had died and left it to Rozier, another Charles County merchant.

- 1679 (approx): Raspin takes possession of Allen’s mill complex with help from Benjamin Rozier.

- 1680: Raspin dies and lists debts to Richard Perkins (prob. payment for work as a cooper) and Benjamin Rozier (and many others).

- 1682: Rozier dies and lists debt to Richard Perkins (prob. still payment for work as a cooper).

- 1683: Our Richard Perkins, cooper, appears in Baltimore County for the first time and lives there for the rest of his life. (At which point all records of the Richard Parkins in Charles County cease.)

Here’s the summary that matters most to the search for our origins: Our Richard Perkins arrived in Maryland in 1674 as a result of business dealings between a group of merchants in Charles County, Maryland and merchants back in England. We have a decade of records showing the interactions of our Richard Perkins, the Maryland merchants, and the English merchants, including (at least) two lawsuits. One lawsuit identified the English merchants as “George Ramsden and John Parkins of the Kingdom of England[,] merchants”, and the other called them “Mr. George Ramsden & Company, merchants in Yorke[shire] in the Kingdome of England”. Those lawsuits were obviously referring to the same George Ramsden, so together they were saying that the English merchants involved with our transported Richard Parkins and the Maryland merchants were George Ramsden and John Parkins of Yorkshire.

This second lawsuit tells us that it no longer matters if there are still parish records in other English counties that haven’t yet been indexed. It means there will never be any need to search outside Yorkshire for our Richard Perkins I. It turns out that we didn’t have to deduce which county these merchants lived in. The two lawsuits together tell us explicitly that the George Ramsden and John Parkins involved in Richard Parkins’s transportation were in Yorkshire.

I’m going to leave the original argument that they must have been in Yorkshire in place and use this new evidence from the second lawsuit as additional verification that the original analysis was correct.

With this new evidence, we have now made this case:

- We have known since the 1800s or longer that the Richard Perkins (I) who first appeared in Baltimore County in 1683 was our ancestor. He seems to have had a brother named William Perkins.

- We have proven that the Richard Parkins who was transported to Maryland in 1674 and lived and worked among the Charles County merchants until 1682 was the Richard Perkins who moved to Baltimore County in 1683. That makes the Richard Parkins transported in 1674 our ancestor Richard Perkins. (In fact, he was the only Richard Perkins in Maryland in his generation.)

- We have proven that the Charles County merchants who brought Richard Parkins and his fellow passengers to America in 1674 were dealing at that time with merchants back in England named George Ramsden and John Parkins. In fact, the year after Richard Parkins, Richard Askew, Isaac Maude, and the others arrived, the Charles County merchants were claiming they owed money to Ramsden and Parkins back in England.

- The Maryland court records explicitly state that the merchants Ramsden and Parkins were located in Yorkshire. Even if records are found that show other Richard Perkinses in other counties, Yorkshire is the only place we will ever need to search for the Richard Perkins whom these merchants transported to Maryland in 1674, whom we have proven was our Richard Perkins.

- So the question becomes, Before the transportation in 1674, was there a place in Yorkshire where merchants George Ramsden and John Parkins lived near transportees Richard Parkins, Richard Askew, Isaac Maude, and others? Historians tell us that they were probably about twenty years old (so, born in 1654 plus or minus a decade or so), and the merchants would have been older.

- A search for all Richard Perkinses (by any spelling) born within thirty years of the right time and anywhere in Yorkshire finds only half a dozen candidates. Perkin[s]/Parkin[s] was not a very common name in Yorkshire. Even so, the Richard Parkin in Halifax matches our Richard in almost every way. His age is exactly what we expect. He was born in 1654. His father’s name was John Parkin. George Ramsden lived in Halifax, too, as did Richard Askew, Isaac Maude, and some or all of the others transported, possibly including Charles County merchant Richard Ambrose’s partner, the mariner John Harrison.

- Richard Parkin of Halifax even had a brother named William Parkin. He is such an outstanding match for everything we know about our ancestor Richard that it not only eliminates the other five candidates (none of whom were even close) but it also makes it extremely unlikely that our Richard was someone else in Yorkshire with the same name but whose records did not survive.

- Therefore, we can conclude beyond a reasonable doubt that the Richard Parkin who was born in Halifax, West Riding of Yorkshire in 1654 and his father John Parkin were our Richard Perkins I of Baltimore County and his father. Our family was the Parkin Family of Western Yorkshire, and in 1674 Richard brought our branch of the Parkin family from our original homeland in Yorkshire to America.

Richard’s surname

Richard Parkin couldn’t write his name, but he could say it: /parkin/ or something more like /parken/. (Those slashes represent pronunciation, not spelling.) The name that most English people pronounced /parkin/ in Richard’s time was recognized by educated people as an old medieval-style nickname for Peter. It was how English speakers had said “Pete” in the Late Middle Ages. Medieval writers had usually spelled it Perkyn, but the the English Great Vowel Shift had caused the pronunciation to change from /per/ to /par/ in most English accents, so people recognized /perkin/, /parkin/, /parken/, etc., as all being the old medieval nickname Pete.

When Richard got off the boat in Maryland and told the clerks (/clarks/) his name was /rekard parken/, they would have recognized both names. The first was his northern-style pronunciation of a given name that had been popular since Richard the Lionheart, and the second was the medieval version of Pete. Regardless of pronunciation, the clerks recognized the old Norman king’s name and wrote it the way they usually wrote it: Richard.

His surname (family name) was more challenging. Maryland clerks had to try to write like Londoners for professional credibility, which meant that in an era when spelling was a matter of taste and style, not standards, they applied a southern sense of style to their record keeping. In southern England in the Middle Ages, Richards Family really meant Richard’s family. (They used a “possessive -s” but didn’t include the apostrophe in those days.) If you wanted to create a surname from a father’s name (rather than an occupation, place, or other description), you would add a possessive s. To southern English ears, Richard, William, Adam, and so on sounded like given names, while Richards, Williams, and Adams sounded like surnames. Richard Williams. William Richards.

“Richard Parkin” would have sounded like two given names, like Richard Peter instead of Richard Peters. That wouldn’t have sounded right, and the name pronounced /parkins/ was very common in southern England, so they either misheard it or just decided to fix it. Either way, the clerks wrote /reckard parken/ as Richard Parkins.

And there was a fashion trend in the 1600s to standardize some spellings by looking back to original, medieval origins for authenticity. The medieval nickname had been Perkyn, so even though almost all English accents, both north and south, pronounced it /parkins/, the most common spelling ended up as Perkins, which is how most Maryland clerks wrote it just a few years after he arrived. Northern-style Parkin had become southern-style Perkins though the pronunciation had only changed from /parkin/ to /parkins/.

In today’s culture, when most English speakers are literate by their teens and the “correct” spelling of your name is treated like personal intellectual property, it’s hard to imagine but the spelling of his name wouldn’t have “mattered a farthing” to Richard. He wouldn’t ever read it. He couldn’t. Most people couldn’t. And it was none of his business anyway. Spelling preferences were a matter between clerks and their bosses in most cases, and even property deeds just had to make it clear which person they referred to. Richard probably continued pronouncing his name as he always had, and the clerks wrote Richard Parkins or Perkins. Richard’s children apparently pronounced the -s, /parkins/ not /parkin/, because no clerk after Richard (I)’s generation ever left it off.

In later generations, English speakers (especially in America) began pronouncing more and more words as they were spelled rather than according to traditional pronunciation, so Perkins was eventually pronounced /perkins/, not /parkins/. There is evidence that our family continued pronouncing it /parkins/ until the 1800s, but that’s another story....

What’s next?

[Further update] In my opinion the above evidence proves that we were the Parkin family of Halifax, so I began researching the story of our family in England. What I found is a family story in England that explains some of Richard’s decisions in America, further confirming that they were our family. Writing this story will take me a while, but I’m working on it.

When I write something, my current plan is to link to it from the Perkins Family History index page (click the ship at the top of the page or the white rose of Yorkshire at the bottom.) The URL will remain GlenCPerkins.com/history/perkins

I can be reached by anyone who can solve the mystery of my email address from this challenging clue (intended to reduce automated spam): I’m at fakename@gmail.com, but instead of “fakename” you use “glencperkins”.