Transported from “overseas”? From where?

Merchants, mariners, and trans-Atlantic deals

In an economy where communication and transportation took weeks or months and people had various things to trade but almost no one had actual money, merchants put together complex, multiway, intercontinental trades with other merchants and mariners. (These merchants were not shopkeepers but people who arranged deals. These mariners were not sailors but operators of ocean transport businesses. Some captained their own ships, and some didn’t.)

A common arrangement was for a Maryland merchant to partner with a mariner to bring servants over from Britain on the mariner’s ship. The merchant and mariner would find people in Britain (usually England) and trade them transportation for an indenture, a service contract. “We will pay for your transportation to America, then you will be required to work for four years to repay the cost.” On arrival, the merchant would claim the headrights, essentially trading transported workers for land warrants. He would find planters who needed land and anyone who needed workers and trade headrights (land) and indentures (labor) for tobacco. The mariner would then take the tobacco back to Britain to sell for actual money (finally), part of which was needed to pay for sailors, maintenance, supplies, and other shipping costs.

There were many variations. Some mariners accumulated headrights so they could retire from the dangerous seas as landed gentry. Putting together these complex trades often required additional merchants (finders, agents, and brokers) on both sides of the ocean, and there were so many ways a multiway deal could go wrong that fraud, failure, and lawsuits were common. And lawsuits left records.

Richard Ambrose and the transportation of Richard Parkins

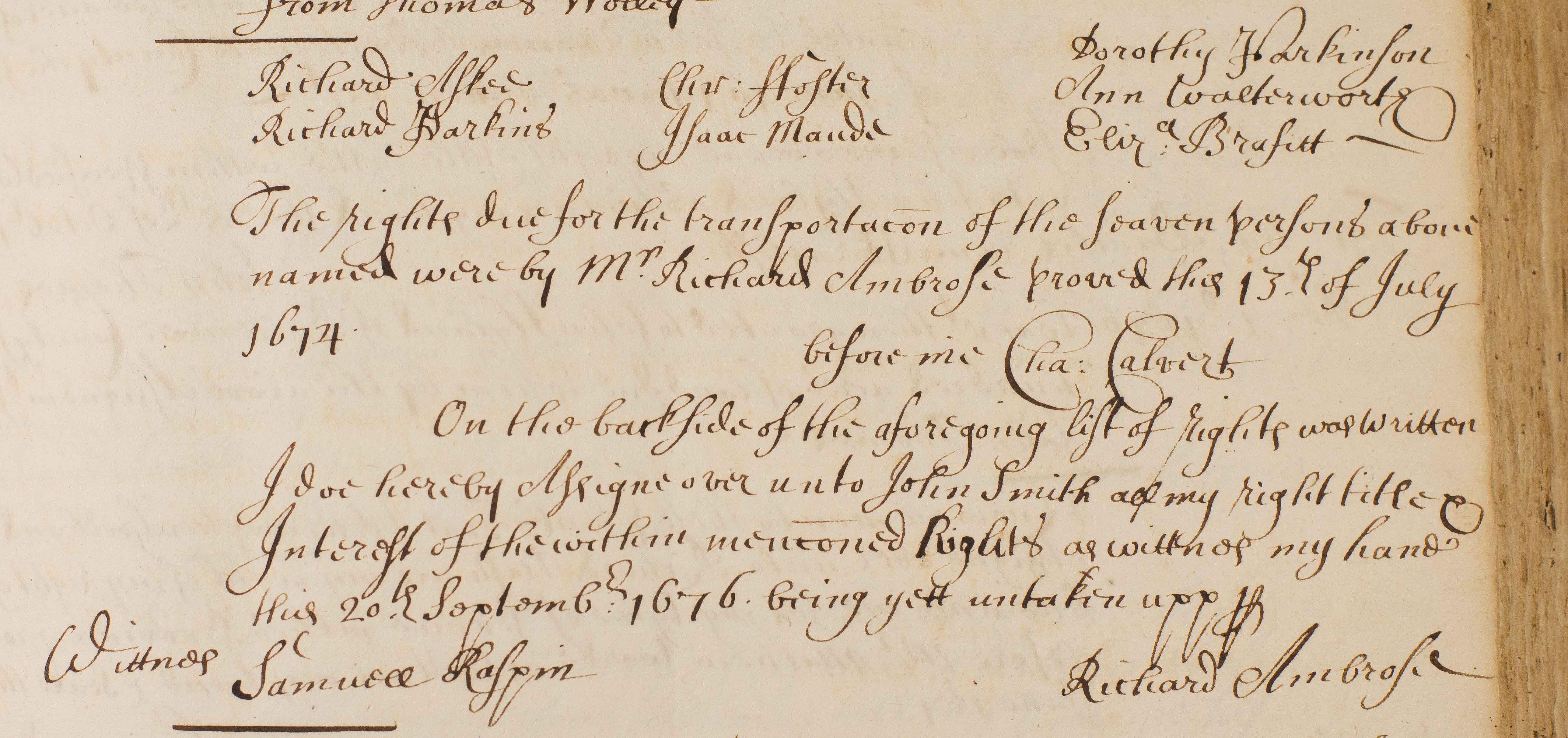

Once again, here is the Maryland Provincial Court record of Richard’s transportation:

Richard Askee, Richard Parkins, Chr[istopher] Foster, Isaac Maude, Dorothy Parkinson, Ann Watterworth, Elizabeth Brafitt.

The rights due for transportac̅o̅n̅ of the seaven persons above named were by Mr. Richard Ambrose proved this 13th of July 1674 before me [Gov.] Cha[rles] Calvert

On the backside of the aforegoing list of rights was written[:]

I do hereby Assigne over unto John Smith all of my right title & Interest of the within mentioned Rights as wittnes my hand this 20th September 1676 being yett untaken upp. Richard Ambrose

Wittnes Samuel RaspinMaryland Hall of Records, Annapolis, MD: Land Office Patents Liber LL (1673-79), p. 512.

Maryland Hall of Records, Annapolis, MD: Land Office Patents Liber LL (1673-79), p. 512.

(Photo by GCP)

This says that on July 13, 1674, a man named Richard Ambrose proved to the court’s satisfaction that he had paid for the transportation into Maryland of seven people, including our Richard Parkins. The court had granted Ambrose the rights due him for the transportation, essentially a voucher for 350 acres of land, which he had transferred to a John Smith (not Capt. John Smith of Jamestown, who was dead by then, but possibly the carpenter John Smith in Charles County).

Since this Richard Ambrose was involved in the transaction that brought our Richard from England, learning more about him might shed some light on Richard Perkins’s English origins.

Richard Ambrose was a merchant from Charles County down on the Potomac River. All transatlantic trade had to go in and out through the mouth of the bay at the far south, so Charles County’s location on the southern border of Maryland was a convenient location for merchants involved in trade between the Maryland settlements and England.

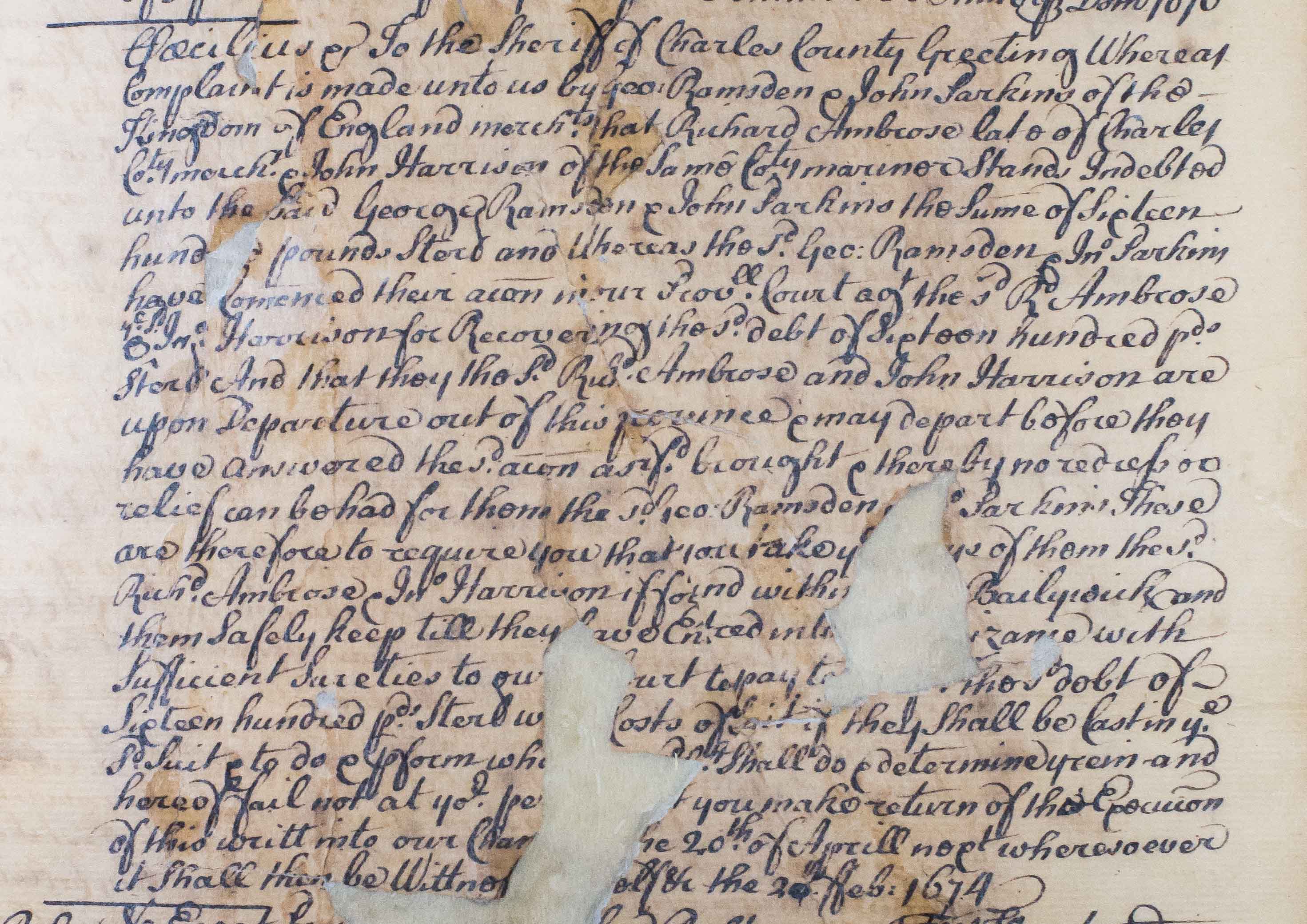

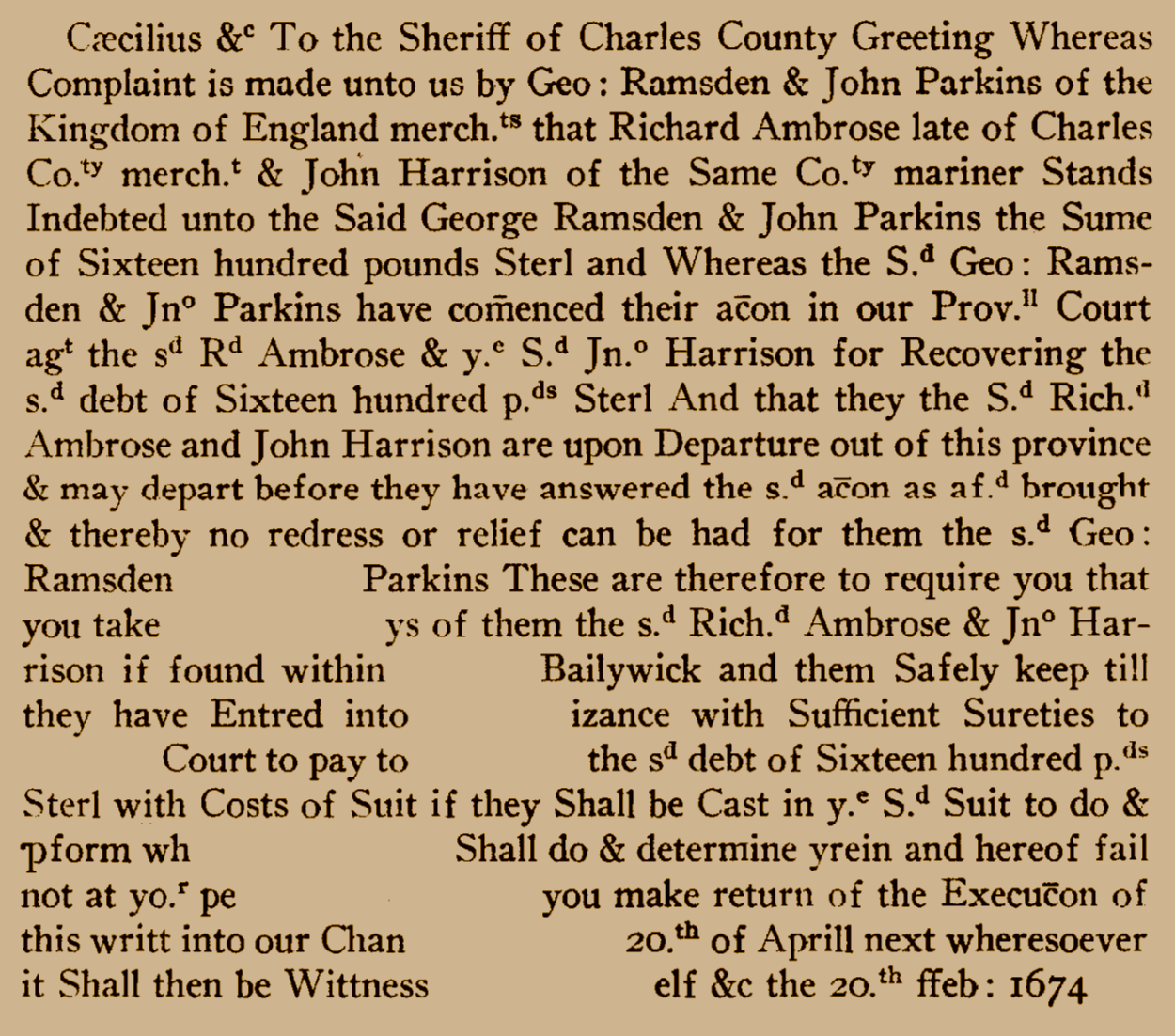

Ambrose was frequently in court, suing or being sued over business deals. One case in particular stands out. The original paper was damaged, so the transcription has gaps, but plenty of information survives to tell an interesting story.

In April 1676, two merchants “of the Kingdom of England” applied, possibly by mail, to the provincial court in Maryland for a writ (a court order) that would force Ambrose and John Harrison (“mariner”) to put up a bond or some form of collateral worth £1600 Sterling. The plaintiffs were suing Ambrose and Harrison over something that referenced a document dated “20th ffeb. 1674”. The plaintiffs claimed that Ambrose and his partner were preparing to leave the province and that even if the courts ruled for the plaintiffs, they might not be able to collect from the defendants unless the court already had their money.

Merchant Ambrose and mariner Harrison were being sued over something from 1674, the year Ambrose and a mariner had transported Richard Parkins across the sea from England. And the names of the plaintiffs in England who were suing them were George Ramsden and John Parkins.

Transcription of Maryland Chancery Court Proceedings 1676, Liber CD, Folio 181, available from the Maryland State Archives.

If you follow that link, you can see from the dates on the other cases that this writ was requested in mid-April 1676. Unfortunately, the original document was damaged, so there are pieces missing, but what remains is enough for our purposes. The transcription (above) is easier to read, but here’s the original document:

John Parkins? Richard Ambrose? A mariner? 1674? These are names and dates we recognize from our Richard’s transportation document. Regardless of the legal or financial details, this lawsuit was clearly about some aspect of the deal in which Richard Parkins and the others were transported by Richard Ambrose and some mariner in 1674. All of these people were involved somehow in the events surrounding our ancestor Richard’s transportation. (Ambrose proved the transportation in July, 1674, and this document refers to something from February, 1674. They were the same year in their system and less than twelve months apart, and it doesn’t matter for our purposes, but just in case you are trying to carefully reconstruct the details, note that February 1674 was seven months after July 1674, because of the way their “Julian calendar” worked.)

Who were these merchants of England, George Ramsden and John Parkins?

If English merchants George Ramsden and John Parkins were jointly suing Maryland merchant Richard Ambrose and his mariner partner, Ramsden and Parkins were probably partners, too, at least for this deal. Not only partners, but partners on the English side of the deal that brought our own Richard Parkins over from England. If they were partners in England, maybe they lived near one another. If the transportation of Richard Parkins ended where Ambrose lived, maybe it started where Ramsden and Parkins lived.

And of course with John Parkins being a Parkins, maybe where John Parkins still lived in England was where our Richard Parkins had come from.

An online search for “George Ramsden” and “John Parkins” together produces a couple of references to the lawsuit against Ambrose in the 1670s and a couple of old records from England: a tax roll and a marriage register. Nothing else. The tax roll is from the West Riding of Yorkshire. (Yorkshire had been the Viking kingdom of Jorvik—pronounced like “Yorwik”—and “-shire” meant county. The Danish Vikings had divided it into three parts, and their word meaning thirding eventually lost the “th” and evolved into the three ridings of Yorkshire.) And if you were searching for the George Ramsden and John Parkins named in the lawsuit, an interesting thing about the West Riding tax roll with their names on it was that it was from the same decade as the lawsuit: the 1670s. The marriage register was also for the West Riding of Yorkshire and also from the mid- to late 1600s.

Yorkshire? That’s way up in the north of England. William Bradford and the Pilgrims came from the West Riding of Yorkshire (on both sides of its border with Nottinghamshire), which isn’t where you would look first for the hometown of a Chesapeake colonist. Most Chesapeake colonists came from southern England, especially the Western Midlands area near the port of Bristol. And the name Perkins is common in the Western Midlands but not up north. It has always seemed likely that a thorough search of parish registers in the Western Midlands for Richard Perkins baptisms was going to be necessary. That would not be easy—so many parishes and probably so many Perkinses.

Our better estimate of Richard’s birthdate would help, but even so, you couldn’t just limit your search to the West Midlands parishes. There were Perkinses all over Britain. You could start in the West Midlands but would have to keep looking just in case.

Or maybe it would be better to start the search in Yorkshire, instead, where George Ramsden and John Parkins lived, because they were involved in Richard Perkins’s transportation.

But that suggests a question:

What if we wanted to find every person in the transported group, not just Richard Parkins, before they left home? Where would we start looking for the others?

If the name Perkins suggests we start our search in the West Midlands, where do the names Askew, Watterworth, or Maude point us? Or Ramsden and Parkins? They were on the British side of the deal but stayed in Britain. And do different spellings of Perkins cluster in different regions? They were the same name, but did spelling preferences cluster regionally? Of course even if they did, would we be discovering the preferences of Richard Perkins or of the Maryland court clerk who wrote about him?

Who knows? We should just try to find more data and see if it tells us anything.