What do the records tell us about Richard Perkins?

NOTE: To make sense of the records, we modern English speakers need to remind ourselves that spelling was not standardized, most people were illiterate and had no opinions about the spelling of their names, their dialects were varied and pronunciation different from ours, and clerks often had to use their imaginations to record names. Perkins was pronounced /parkins/ by most people in Maryland, just as Berkeley was pronounced /barkly/, clerk as /clark/ and so on. The same name could be spelled Perkins, Parkins, Perkin, Parkin, Parkynn, Parkine, Parking, and many other ways.

Our ancestor, Richard Perkins I of Baltimore County, first appears in the Baltimore County records in 1683 when he has 100 acres of land surveyed and patented. His land was at the head of Mosquito Creek, just south of where the Susquehanna River flows into the Chesapeake Bay. The name Richard gave his land would probably be spelled Parkinton today. The name means Parkin, Parkins, or Perkins farmstead.

Mosquito Creek is located on what is now Aberdeen Proving Ground, a military base in Harford County, Maryland, but neither the military base nor Harford County existed during Richard’s lifetime. When he bought his land, it was part of Baltimore County, and most of the land around him was owned by the powerful Utie family and their in-laws and friends.

“Parkington” surveyed 17 Nov 1683 for R’d parkins at ye head of Muskato Creek at a bounded tree in a swamp now Sold to W’m FrisbySource: The Rent Roll of Anne Arundel Co., MD, Herring Creek Hundred, p. 136. [Note: This land was in Baltimore Co., Spesutia Hundred.]

The summary here following covers pages 24 to 62 of the record liber R M No. H S, which carry transcribed records from an older book called E No. 1, no longer extant.

[...]

Survey certificate, December 15, 1683, Thomas Lightfoot, deputy surveyor, stating that he has laid out for Richard Perkins, cooper, the 100-acre tract “Perkinson” at the head of Musketa Creek, bounded by the tracts “The Grove”, “Mascalls Humer”, and “Bever Neck”, to be held as of the manor of Baltimore. Copy certified by Deputy Clerk John Yeo.Source: Scisco, Louis Dow. “Baltimore County Land Records of 1683”. Maryland Historical Magazine (Journal of the Maryland Historical Society), vol. 32 (1937), no. 1, p. 34.

Richard Perkins settled at the head of Mosquito Creek, Baltimore Co., MD about 1683. A survey certificate dated 1683 Dec 15 by Thomas Lightfoot, Deputy surveyor, recorded that he laid out a tract of 100 acres for Richard Perkins, cooper, later called a planter. The tract called “Perkinson” was situated at the head of Mosquito Creek and was to be held as of the Manor of Baltimore. It was bounded by tracts called “The Grove”, “Mascalls Humor” and “Beaver Neck”. This was part of a 1200 acre tract laid out for Edward Beedle of Baltimore County, MD the 31 Jul 1683. Rent 5 shillings sterling or gold to be paid.Source: Patents. ID4IL#C-Folio 165, 166.

“Perkinson” would have been pronounced /parkinson/, which was a common name then and now, but it wasn’t Richard’s name. Richard Perkins’s neighbor and possible in-law, Richard Ives, called his land “Iveton”, the Ive or Ives farmstead. Our Richard called his Parkinton, the Parkin (or Perkin or Parkins or Perkins) farmstead, which ended up spelled Parkin(g)ton or mistaken for the name Parkinson.

These records of his first-known land purchase in 1683 say that he was, or had been, a “cooper” (barrel maker). Maybe that’s what he did during or just after his indenture.

Beginning in 1683, there were more than twenty years of official records of transactions involving our Richard Perkins in Baltimore County. So, if Richard Perkins had been an indentured servant prior to that, like the majority of people showing up in Maryland at that time, we could make some estimates about other events in his life by “profiling” him—matching what we know about him to the typical life pattern of Marylanders who arrived as indentured servants in his generation.

A bill considered but not passed by the 1639 [Maryland] Assembly would have required servants arriving in Maryland without indentures to serve for four years if they were eighteen years old or older and until the age of twenty-four if they were under eighteen. The gap between time of arrival and first appearance in the records as free men for the men under study suggests that the terms specified in this rejected bill were often followed in practice.

[...]

Although custom demanded that servants be granted the rights to fifty acres of land on completing their terms, actual acquisition of a tract during their first year of freedom was simply impracticable, and all former servants who eventually became freeholders were free for at least two years before they did so.Menard, Russell R., “From Servant to Freeholder: Status Mobility and Property Accumulation in Seventeenth-Century Maryland”, The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd. Series, Vol. 30, No. 1, Chesapeake Society (Jan. 1973), pp. 49-50. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1923702

The pattern was that after arrival, a four-year indenture was the usual term for a servant 18 or older. A 17-year-old would serve seven years, a 16-year-old eight years, and so on, to reach 24. Then he would have received 50 acres as a headright but, as Menard says, he would still have needed at least two more years to actually acquire the land, so six or more years after arrival to acquire 50 acres. But our Richard acquired 100 acres, not just 50, which would have taken another couple of years or so. If he had been 18 or older on arrival, that would mean a total of roughly 8-10 years, and several years longer if he had been under 18.

So, if Richard arrived as an indentured servant at age 18 or older like most others and took 8-10 years to reach the point where he could acquire his 100 acres of land in 1683, he would have been transported to Maryland in the mid-1670s. If under 18 with a longer indenture, his arrival date would have been a few years earlier—1670 or so.

The large number of young, single, male indentured servants arriving at that time meant that a single man showing up in Maryland was very likely to be one of the transported servants. Even so, there were other possibilities. If instead of being transported as a servant, Richard arrived as a free immigrant, he would have received a 100-acre headright immediately, 50 for transportation and 50 for being a new worker. In theory you could claim the immigrant headrights even if you were moving in from another colony, but you had to prove it. It would still have taken him some time to have the land surveyed and patented, so if this was done in 1683, he would probably have immigrated in 1682 or so.

And if he had been born in Maryland a free man, he could have begun buying land in his early- to mid-twenties. If this were the case, buying 100 acres in 1683 would suggest a birth around 1660 or a little earlier.

So, we’re looking for a Maryland record of a Richard Perkins that shows either:

- [Most likely] Transportation in the mid-1670s for someone 18 or older

- Transportation in the late-1660s for someone under 18

- Immigration in about 1682 or a bit earlier (including immigration from another colony)

- Birth/baptism in 1660 or so, more likely earlier than later

We need to list all the records of any Richard Perkins transportation, immigration, or birth in Maryland prior to 1683 and compare them to see which is most likely to be our Richard Perkins. As it turns out, this entire “list” contains only one item, and it’s a perfect match to the most likely scenario:

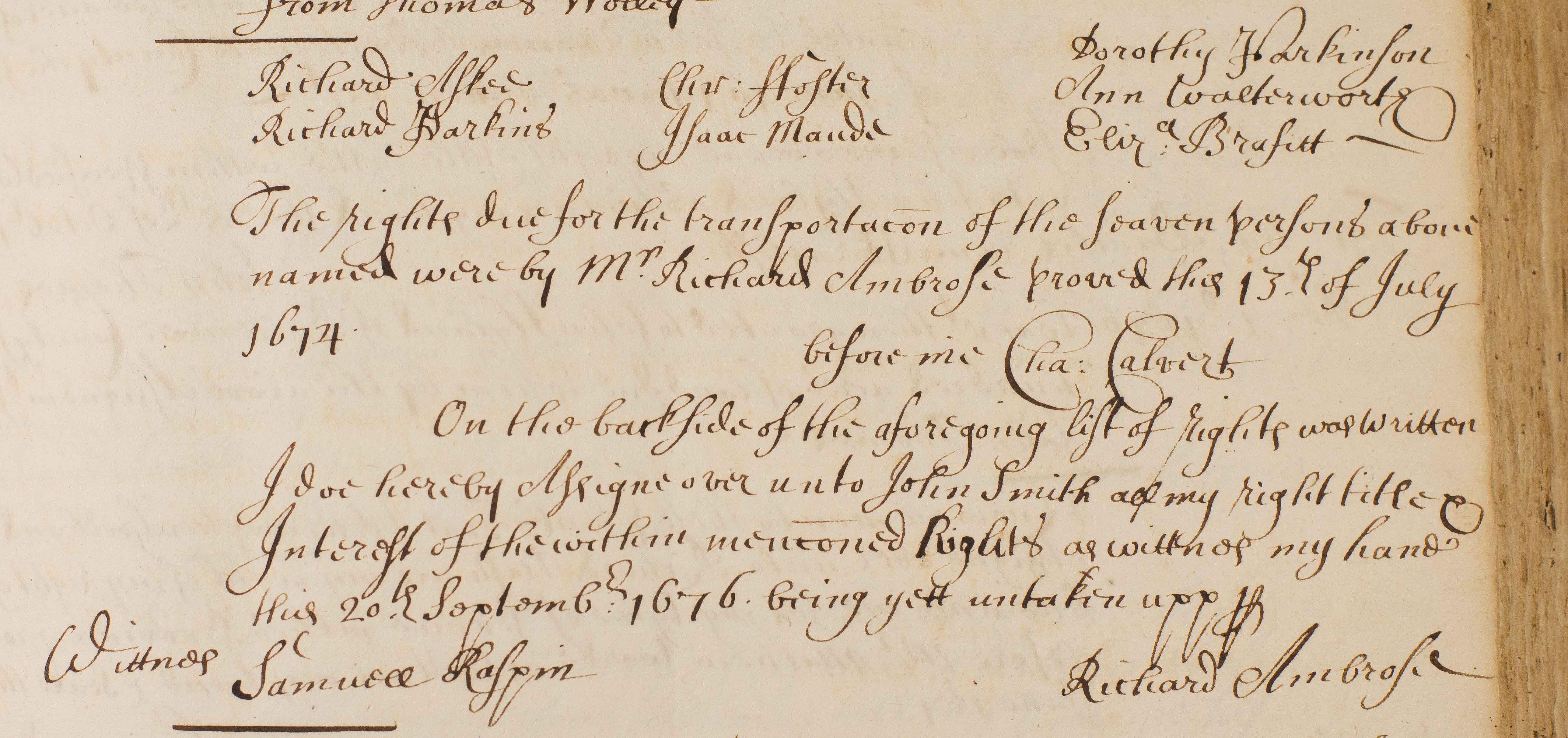

Richard Askee, Richard Parkins, Chr[istopher] Foster, Isaac Maude, Dorothy Parkinson, Ann Watterworth, Eliz[abeth] Brafitt.

The rights due for transportac̅o̅n̅ of the seaven persons above named were by Mr. Richard Ambrose proved this 13th of July 1674 before me [Gov.] Cha[rles] Calvert

On the backside of the aforegoing list of rights was written[:]

I do hereby Assigne over unto John Smith all of my right title & Interest of the within mentioned Rights as wittnes my hand this 20th September 1676 being yett untaken upp. Richard Ambrose

Wittnes Samuel RaspinMaryland Hall of Records, Annapolis, MD: Land Office Patents Liber LL (1673-79), p. 512.

Maryland Hall of Records, Annapolis, MD: Land Office Patents Liber LL (1673-79), p. 512.

(Photo by GCP)

Once again, this perfect match is the only record of a Richard Perkins (by any spelling) coming to Maryland in that era:

Extensive searches have been conducted by at least two different branches of the families who have descended from Richard Perkins, including lengthy searches by paid professional researchers and genealogists. These searches have never established a Richard Perkins coming to Maryland other than the Richard Perkins (Parkins) who was transported in 1674.

Perkins, Eugene H. The First Mormon Perkins Families, p. 3. (2008).

This Richard Parkins perfectly fits the timeline for our Richard arriving as a typical 18-or-older indentured servant. And this Richard Parkins’s indenture would have ended in about 1678.

If Richard was 18 or older, his age range was roughly 18-24. The upper limit could be a bit more flexible, but 20-21 is still the most likely (according to historian James Horn’s quote above). That would put his birthdate range at 1650 (or a bit earlier)-1656, with 1653-1654 the most likely.

What about church records?

So land and other legal records are telling us that this must be our Richard Perkins, but there are also church records. Do they lead us to a different conclusion? What do the church records tell us about the Richard Perkins who lived at the head of Mosquito Creek and his family?

The original Spesutia Church, the only one in St. George’s Parish, was just a couple of miles south of Richard’s first property, and St. George’s Parish records were well preserved.

They show that in 1689, six years after buying his Mosquito Creek land, Richard and his wife “Mary” baptized their first child, Richard (whom we call “Richard II”). The same parish records show that this first son later named his own first son Richard (“Richard III”), who would later be known as “Tomahawk Dick Perkins” on the North Carolina frontier.

In 1692 Richard I and Mary had a second son and named him William.

They had children in 1689, 1692, 1695, 1697, 1699, and 1701, and there were no subsequent mentions (in wills, land, legal, or church records) of any child other than the ones born on these dates. This makes it very likely that Richard II was their first child, and this regular pattern of births makes it reasonable to assume that Richard I married Mary in about 1688, the year before Richard II was born.

If his indenture ended in about 1678, he emerged right into the most chaotic and violent rebellion in Colonial American history other than the Revolution itself: Bacon’s Rebellion in the Chesapeake colonies. Tobacco prices had been falling for decades, reducing everyone’s wages, but government prices for such things as land surveys were not reduced and taxes were rising. More young men had to sell their headrights for food, leaving them landless, and the most conveniently located land had already been claimed anyway and consolidated into large plantations by a few wealthy families. To get land, many former servants had to go deeper into unsettled areas where they were vulnerable to Indian attacks. The aristocrats who ran the government lived in safer areas and profited from trade with the Indians, so they repeatedly denied the frontier settlers’ requests to send militias out to push back the Indians.

The sons and daughters born to local aristocrats were born in the usual 1:1 male:female ratio, and they married each other. A minority of servants were female, and their lives in servitude were often miserable, but if they survived, they could quickly and easily marry men with land.

But the great majority of servants emerging from indentures were male. They had fewer options. Settled areas had more local births than the frontier, so wives were a little easier to find, but land wasn’t available. In less-settled areas, up the rivers or up the Chesapeake in Maryland, there was more land but fewer local births, so wives were hard to find.

These men had risked death as virtual slaves in the Chesapeake for the chance that, if they survived, they could have real lives as self-sufficient heads of families. For most, this meant they had to obtain both land for farm income and a wife as soon as possible after the end of indenture. They needed to get started making money and babies. The clock was already ticking, their schedules tight, and more and more of them were discovering that there would never be land or a wife for them. They felt hopeless. They had risked their lives for nothing.

This created a volatile situation, and in 1676, when Richard Perkins was in the middle of his own indenture, a violent incident between settlers and Indians ignited a rebellion in Virginia that quickly spread into Maryland. Mobs of settlers, many of whom had emerged from servitude and found no path forward, attacked Indians, aristocrats, and government soldiers. Led by a recently arrived young aristocrat named Nathaniel Bacon, they turned the Susquehannocks in Maryland from allies to enemies, burned Jamestown to the ground, and declared themselves the new government of the Chesapeake colonies.

Nathaniel Bacon had arrived the same year as Richard, but he was a free and wealthy immigrant, not a servant like Richard. He enjoyed a good life briefly, jumped on the wave of rebellion and became its leader then—like so many other newcomers to the Chesapeake—abruptly died of dysentery. He had survived about two years and died halfway through Richard’s indenture. After Bacon died, the rebellion became disorganized, the king sent troops, hanged some leaders, pardoned others, and killed a lot of Indians.

But despite the collapse of the rebellion, the problems that had inflamed it were still the realities of life for a young man in Maryland emerging from his indenture in about 1678. The government figured they had dodged a musketball when Bacon died but that there would be more rebellions by the settlers unless something changed. The tobacco economy was dying, and indentured servants were not worth the risk. The new Lord Baltimore (Charles Calvert) was fed up with the headrights system and announced in 1676 that it would soon be discontinued. Corrupt land officials took their time (until 1683) shutting it down, issuing themselves headright warrants that could be spent like cash, then turned to both Indian and African slavery as a “better” source of labor than indentured servitude.

We know that there was a “Richard Parkins” transported into Maryland in 1674. The provincial court declared it proven. If he was our Richard I, he made it just as the headrights door was closing, survived his indenture until 1678, and entered the dying tobacco economy in a place with few women where he needed to earn a living and find a wife.

Five years after the Richard Parkins who was transported emerged from his indenture, government records show that our Richard Perkins had earned enough to obtain his first hundred acres of land. Ten years after transported Richard emerged, church records show that ours finally got himself a wife and started having children. The timelines for transported Richard and our Richard match. They were the same person.

And if Richard was 18-24 with 20-21 most likely when transported in 1674, spent four years as a servant, then got married ten years after that, he would have been 32-38 (34-35 most likely) when he and Mary were married in 1688. They had six children over the following 12-13 years, and Richard died in 1705. That would have been about 30 years after he was transported, so he died at about age 49-55 (51-52 most likely).

Forty-five was approximately the expected lifespan of a Maryland planter who survived his first few years. Transportation record, land records, church records, and statistical life expectancy all line up.

Any other records of Richard Perkins?

Yes. After 1683, all records of a Richard Perkins in Maryland were in Baltimore County, but prior to 1683, there were three mentions of a Richard Perkins, all of which involved merchants down in Charles County along the Potomac River. The first was the record of his transportation in 1674 (above) and of the resulting headrights being transferred in 1676 from a Charles County merchant, Richard Ambrose, to someone named John Smith. There were several John Smiths in Maryland, not surprisingly, but one in Charles County was a carpenter. And after his indenture, Richard was said to be a barrel maker. This transfer of headrights from Ambrose to Smith was witnessed by another Charles County merchant named Samuel Raspin.

The second mention was in the inventory of Samuel Raspin’s estate when he died in 1680, which listed Richard Perkins as someone Raspin owed money to (Charles Co. Probate: Liber 7A:197, 1680-Aug-13). By 1680, the Richard Perkins who was transported in 1674 would have ended his indenture and begun working for pay in order to obtain his land. As mentioned earlier, the Chesapeake economy had very little that could be used as money—no credit cards, no paper money, and very few coins (mostly Spanish). They had to resort to using tobacco for money, but tobacco was only harvested once a year. Hired workers would be fed and housed, but their wages (minus room and board) would be carried as debt until the “money” was harvested and debts could be settled. At the time of his death in 1680, Samuel Raspin was operating and upgrading a mill complex (multiple mills, a blacksmith shop, and possibly other services) that today is an archaeological site called “Allen’s Mill” in Zekiah Swamp above the head of the Wicomico River in Charles County. Raspin’s estate showed outstanding debts to 172 people, including Richard Perkins and John Smith. Many of those people were prominent members of society, but surely many of them worked for Raspin. Allen’s Mill processed and prepared tobacco and grain grown upstream for overseas export. Hogshead barrels were the standard cargo container. It seems likely that John Smith and Richard Perkins were woodworkers at Allen’s Mill.

The third mention of Richard Perkins prior to our Richard’s purchase of his first land in Baltimore County in 1683 was just one year earlier. In 1682, a major landowner and former sheriff of Charles County named Col. Benjamin Rozier died and listed Richard Perkins as one of the many people his estate owed money to (Charles Co. Probate: Liber 7C:98-127, 1682-May-25). Rozier’s final real estate deal had been arranging the foreclosure of Allen’s Mill and transfer of ownership from John Allen to Samuel Raspin. Unfortunately, Raspin died as this was taking place, resulting in several lawsuits over mill ownership. Since Rozier’s estate also owed Richard money in 1682, it appears that Richard was still working at Allen’s Mill or nearby.

All records of the Richard Perkins who was transported in 1674 and involved with Samuel Raspin and his Charles County associates end in 1682, and in 1683, our Richard Perkins buys his first land up north in Baltimore County and begins his life as a land owner and future head of a family. From 1683 until his death in 1705, all records of an adult Richard Perkins in the Province of Maryland were our ancestor in Baltimore County. The Charles County Richard Perkins who was transported in 1674 clearly moved north to Baltimore County in 1683 and became “our” Richard Perkins.

So, this is what we have:

- The name Perkins is the same name whether spelled Perkins, Parkins, Perkin, Parkin, etc.

- At the time and place our ancestor, Richard Perkins, lived in Colonial Maryland, most men like him arrived as indentured servants and lived their lives on a tightly constrained schedule—a sort of life template.

- Our Richard Perkins entered the public record in Baltimore County, Maryland 1683 and is found in many different kinds of records there, both governmental and ecclesiastical (church), over the subsequent years.

- Matching the many records of his life to the standard template of his neighbors who had arrived as indentured servants allows us to estimate quite closely when he was probably transported. For the much less likely scenarios of immigration or local birth, we can also estimate dates.

- Searching the record for all instances of a Richard Perkins transportation, immigration, or birth in Maryland before our Richard definitely lived there (in 1683) yields only one arrival: a record of a Richard Parkins being transported into Maryland as expected and exactly when the template says he would have been.

- There are also two records of the Richard Perkins who was transported still living among the merchants whose names were on his transportation record but working for money after his indenture would have ended.

- That work for money in Charles County by the Richard Perkins who was transported in 1674 ends the year before our Richard Perkins shows up in Baltimore County and buys his first land.

- All records that we have of our Richard’s life are consistent with his having been transported to Maryland as an indentured servant in 1674 and of his being the expected age (18-24, with 20-21 most likely) of an indentured servant at that time.

- It’s hard to imagine what an alternative record of our ancestor’s arrival would have to look like for it to fit the evidence better than this.

Every piece of evidence we have about every aspect of our Richard Perkins’s life matches the one, lone record Maryland has of someone by that name entering at that time and in the way he probably entered. And that one record, which matches our Richard so well, matches no one else. Maryland records show just one Richard Perkins arriving and just one living in Maryland after that arrival in Charles County until about 1682 and in Baltimore County beginning in 1683. The one who arrived and the one who was living there for decades after the arrival were the same man.

There is no need to look for a better explanation of our Richard Perkins’s arrival in Maryland. The “Richard Parkins” who was transported to Maryland as an indentured servant in 1674 was our ancestor, Richard Perkins I.